“On the other side of the Jordan, in the land of Moab, Moses undertook to expound this Teaching, saying…” (Deuteronomy 1:5).

Our teacher Ibn Ezra said in his commentary on Deuteronomy 1:3, “And if you understand the secret of the twelve, as well as ‘and Moses wrote,’ (Deuteronomy 31:22) ‘and the Canaanites were then in the land’ (Genesis 12:6), ‘On the mount of the Lord there is vision,’ (Genesis 22:14), ‘His bedstead, an iron bedstead, is now…’ (Deuteronomy 3:11), you will know the truth.”

What is this truth Ibn Ezra is hinting at? The book of Deuteronomy is also known as Mishneh Torah, the “repetition of the Torah.” Its name testifies that it is not a book like the other books, but a repetition of them. It has already been said in the Gemara, in tractate Megillah 31b, “Abaye said: according to the Tannaim, this rule [that when reading the Torah in public, portions of curses should be read by one person only] is valid only for the portion of the curses in Leviticus, but the portion of the curses in Deuteronomy may be divided between several readers. Why? The first are said in plural, and Moses said them guided by the Divine, but the latter are in singular and Moses said them on his own.” These words are amazing. The Gemara says that the whole section of curses in Deuteronomy (in the portion of Ki Tavo) was not said by the Holy One, blessed be He, but that Moses said them on his own mind (and therefore there is no sanctity in this portion, and it may be divided between different readers). We find that there are sections in the Torah which do not come from the Divine, but are from flesh and blood!

Because of this we will devote this week’s portion to the greatest of Biblical commentators, Rabbi Abraham the son of Meir Ibn Ezra, who said of himself in the introduction to his commentary: “My commentary is based on the fifth way, and it is honest in my eyes in the face of G-d whom alone I fear, and I will not show favoritism in the Torah, and I will seek well the grammar of each word with all my might and afterwards I will explain it as well as I can.”

Baruch Spinoza, one of the first Biblical critics, in his “Theological-Political Treatise” (chapter eight) quoted the words of Ibn Ezra cited above and from that he proved that Ibn Ezra supposed that not Moses wrote the Torah, but that someone else, later. All who seek truth should read this fascinating book. The rabbis forbade reading it and they had good reason: his sharpness and his deep wisdom, and in his words the truth can be recognized.

We will bring his words in context and we will add our own. But to ease the way for those who seek, we will also bring the words of those who stick to the traditional commentaries. This is the supposition of the Gemara in Tractate 98a, “And even if you say that the whole Torah is from the Heavens aside from this one verse which the Holy One, blessed be He, did not say, but Moses himself did, this is ‘and G-d’s word he desecrated’.” (Yet the Gemara itself, in Tractate Megillah, says exactly these things…see above), and each person should choose the way to follow.

First we will say that one who looks at the whole Torah will see that, according to the plain meaning, the author of the Torah is not Moses but another who speaks of Moses, for it says, “And G-d spoke to Moses,” not “And G-d spoke to me.” What do the Biblical commentators say about that? This is what Nachmanides writes in the introduction to his commentary: “But Moses our teacher wrote the stories of all the early generations and related to himself and his story and what happened to him in the third person and therefore it says, ‘And G-d spoke to Moses and said to him’ as one who speaks of two others…and the reason for writing the Torah this way is that it preceded the creation of the world, not to mention the birth of Moses our teacher, and we have it as tradition that it was written as black fire on white fire, and Moses is as a scribe, copying from an ancient text, and therefore he wrote it as a spectator from aside.” (And this reason, aside from taking its testimony back before the creation of the world, answers one question and raises a thousand more. If everything was determined before creation and written and sealed in a book, how can I sin and why should I be punished. The wise one will understand). We wrote, in the portion of Masaey, that tradition and “secret” (sod) are the first escape of “wise” people whose arguments have run out.

And now we will return to Ibn Ezra’s commentary. This commentary was said on the verse, “These are the words that Moses addressed to all Israel on the other side of the Jordan,” and it is clear to Ibn Ezra and to us that the writer of this verse was in the Land of Israel, west of the Jordan, and therefore said, “on the other side of the Jordan.” But Moses himself never entered the land, so how could he write “on the other side of the Jordan”?!

“The secret of the twelve”–even though it is not completely clear what Ibn Ezra meant, in our opinion it is as R’ Joseph the son of Eliezer Bonfils wrote in the 14th century in his book “Tzafnat Pa’aneach” (which is a commentary on Ibn Ezra, and it is recommended to everyone who seeks truth to read that book): “‘The twelve’ are the last 12 verses of the Torah (Deuteronomy 34:1-12), and he [Ibn Ezra] meant that all the text from ‘And Moses ascended’ until the end of the Torah was written by Joshua.”

“Moses wrote down this Teaching and gave it to the priests, sons of Levi,” Deuteronomy 31:9. “This” Teaching? What does the Scripture speak of? Against your will you will see that if Moses wrote the Torah that he gave the Levites then the Levites carried a Torah without this verse, and another author is the one who tells what Moses wrote and gave the Levites.

Rashi: “And Moses wrote and gave it”–when it was fully finished he gave it to the members of his tribe.” According to Rashi Moses did not give the Torah to the Levites in that place, but continued to write the following portions and even that verse itself which says he wrote a Torah and gave it to the Levites, but in reality he did not then give it to them, for he kept on writing…

“And the Canaanites were then in the land,” and his intention in this hint is simple, that in the days of the Torah’s author the Canaanites were not in the land (and therefore he wrote “then”. In the time of Moses the Canaanites were definitely in the land! Against your will you must say that it was written later, and we already went on about this at length in the portion of Lech Lecha part two.

“And Abraham called that place YHWH Yiraeh, whence the present saying, ‘On the mount of the Lord there is vision'” (Genesis 22:14).

From the words “whence the present saying” we deduce that it was said at a later date. The word asher in the verse is translated as conditional, “whence,” as in Targum Onkelus, “ubchen yitamar kyoma hadin.” He also translated thus on Exodus 6:6, “Say, therefore, to the Israelite people.” The location of the Holy Temple was not, after all, chosen in the time of Moses, as written in Deuteronomy 14:23, “You shall consume…in the presence of the Lord your G-d in the place where He will choose to establish His name.”

And how did our rabbis interpret this? Rashi explains: “present–future days.” The Rashbam explained: “Therefore they will say today and in the future, on G-d’s mountain did the Holy One, blessed be He, show Himself to Abraham.” See how our commentators come and distort the Scriptures: The Torah says “present” and Rashi says “future days,” the Torah says “present” and the Rashbam says “and in the future.” Go and consider whether also on the verse “And the Lord has affirmed this day that you are, as He promised you, His treasured people” (Deuteronomy 26:18) Rashi and the Rashbam would say that it was only in the future or future days that they would be His treasured people?

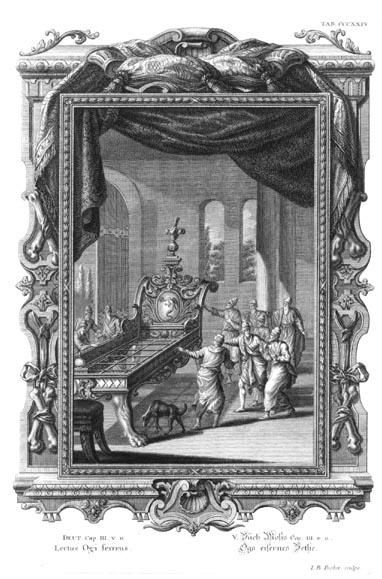

“Only King Og of Bashan was left of the remaining Rephaim. His bedstead, an iron bedstead, is now in Rabbah of the Ammonites; it is nine cubits long and four cubits wide by the cubit of man.” From the way the verse is written we can deduce that it was written after Moses’s death, for Moses fought Og and won out over him in the fortieth year after the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, just a short time before Moses’s death; what would be so remarkable about Moses saying ‘is now in Rabbah of the Ammonites’? Of course it is in Rabbah of the Ammonites, he was killed only a short time before, and there is no point stating this in the Scripture unless it were written a long while after the death of Moses and not by him. The Rashbam explains that Og’s bedstead was from the time he had been a baby. The Scripture wanted to glorify his size, even when he was a baby, and therefore also said that the bedstead was of iron, for had it been of wood it would have broken. Of all this there is no sign nor mention in the Scriptures.

But you, the reader who desires knowledge, check these matters with no favoritism. And anyway, know that to all the opinions, all comes from the text itself, with no additions from tradition, brings to one clear conclusion–that the author of the Torah was not Moses. All that remains for a thinking person is to decide between two approaches: whether to accept things as they appear or accept and believe in tradition, even if it contradicts and distorts the Scriptures.

Since we are dealing with Ibn Ezra we saw fit to bring a summary of his words as brought in various portions.

In the portion of Vayishlach, on the verse Deuteronomy 34:6, “and no one knows his burial place to this day,” “These are the words of Joshua, and it is possible he wrote this at the end of his life.”

In the portion of Tzav we cited Ibn Ezra on Exodus 20:1, “and the Ten Commandments written in the portion of V’etchanan are the word of Moses.”

In the portion of Kedoshim we brought Ibn Ezra’s opinion about why the punishment for one who sleeps with two sisters is not mentioned and how it is possible that our forefather Jacob married two sisters.

And in the portion of Emor we brought his commentary on the “leafy tree: which is not the myrtle (contrary to the words of the Gemara): “The leafy tree is an argument against our ancestors, for the tree of the myrtle species is not tall, and there are two species, one tall and one short.”

In the portion of Naso we brought Ibn Ezra’s puzzlement at the count of the Levites who did not multiply, though they were not included in the decree of death in the desert.

And in the portion of Chukat we brought his opinion that the prohibition against drinking water at the time of tekufa was witchery and the early ones only forbade it to scare the public into making repentance.

And we will add here our own words. Moses our teacher speaks to the people of Israel before they enter the Land of Israel and sometimes he adds in clarification of things, sort of parenthetical words within his statements. This is what seems to happen in Deuteronomy 2:9-14, “And the Lord said to me: do not harass the Moabites or provoke them to war, for I will not give you any of their land as a possession; I have assigned Ar as a possession to the descendants of Lot. (It was formerly inhabited by the Emim, a people great and numerous, and as tall as the Anakites. Like the Anakites, they are counted as Rephaim, but the Moabites call them Emim. Similarly, Seir was formerly inhabited by the Horites, but the descendants of Esau dispossessed them, wiping them out and settling in their place, just as Israel did in the land they were to possess, which the Lord had given to them.) Up you now! Cross the Wadi Zered!” From the implication of the verse “just as Israel did in the land they were to possess” it seems clear that this whole section was written after the people of Israel conquered their land. If so, it was not Moses who added the parenthetical matter. (And pay heed to the change in person, “which the Lord had given to them,” and then “Up now! Cross” which also shows the change in writers and styles.)

And what do the Biblical commentators say of this? The Hezkuni: “Just as Israel did: the tribes of Gad and of Reuben. In the land they were to possess: Moab.”

You see how the Hezkuni distorts the Scriptures. In the Torah it is written “Israel” and he says “the tribes of Gad and of Reuben.” In the Torah it is written “in the land they were to possess” and the Hezkuni writes “the land of Moab.”

And about the verse of Deuteronomy 3:14, “[He] named it after himself, Havvoth-yair, as it is until this day,” we have already explained at length in the portion of Vayishlach; see there.

So we ask: how dare anyone, be he as great as he may be, be the question before him as difficult as it may be, to distort and falsify the very words themselves? To say that “present” means “future,” to say that “Israel” means “Gad and Rueben”? And so in many places.

It is appropriate to conclude here with that sentence by Ibn Ezra which we have become accustomed to repeating and which was cited in pamphlet 8:“How is it possible that a man should say one word and mean another; one who says this would be thought mad, etc., and he’d better say he does not know rather than twist the words of the Living G-d.”

Words of True Knowledge