Parshat Tzav

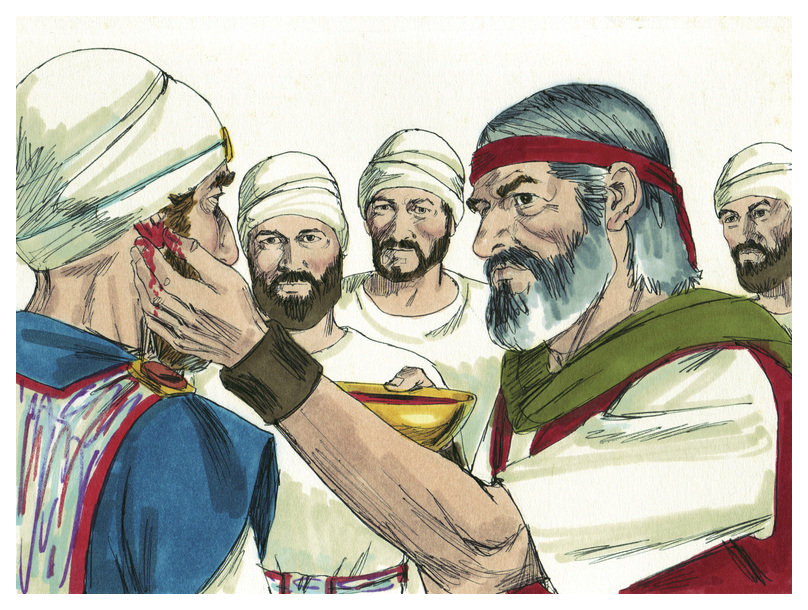

“‘Take Aaron and his sons…’ and Aaron and his sons did all the things that the Lord had commanded through Moses” (Leviticus, chapter 8).

The whole eighth chapter in our portion speaks of the anointing of Aaron and his sons for the priesthood. This section is the dedication, as G-d had commanded Moses in Exodus 29:1-37.

Again, as we have seen in previous portions, we see here a duplication of an entire chapter; the only difference is that in Exodus G-d commanded Moses and in our chapter we see the genuine action.

When were Aaron and his sons anointed? Rashi on 8:2 writes, “This section was said seven days before the Tabernacle was built; there is no chronological order in the Torah.”

Go see the chaos which the person who sewed the scrolls together created here (about the order of the scrolls see our words on the portion of Pekudeiand here, below).

In Exodus chapters 25-31 we have G-d’s command to Moses about the Tabernacle and its vessels and the anointing of Aaron and his sons (chapter 29). The Golden Calf and the receiving of the second set of Tablets are in chapters 32-34, even though they happened before the commandments to build the Tabernacle (see Parshat Pekudei).

Then, in chapters 35-40, the Scripture details the actual building of the Tabernacle but forgets to include there the anointing of Aaron and his sons, though that happened seven days before the Tabernacle was built.

It is only in the book of Leviticus, after a discussion of the sacrifices, that chapter eight details the anointing of Aaron and his sons. (We see that the building of the Tabernacle is not over; the Scripture returns to it in Numbers 7:1, “And on the day Moses finished building the Tabernacle…the leaders of Israel brought sacrifices.” The dedication of the Tabernacle is detailed, and once again the building of the Tabernacle is mentioned in 9:15, “And on the day he built the Tabernacle…”.)

The Ramban, though he agrees that there is no chronological order in the Torah, understood that our case is very odd. Why and wherefore was the building of the Tabernacle detailed, but the anointing of Aaron and his sons was written about only in Leviticus? His heart stood and screamed out, on Leviticus 8:2, “And why were the words of the living G-d overturned, especially as he was commanded during the incident of the day in the first month about the whole building of the Tabernacle and the dressing of Aaron and his sons and the anointing of them all. There it speaks of Moses’s actions in building and does not mention anything about Aaron and his sons until here. How did one matter get separated into two parts and the earlier get placed later?”

Therefore the Ramban wrote that the anointing of Aaron and his sons was after the building of the Tabernacle and the commandment about the sacrifices. Know that the Ramban disagrees not only with Rashi, but also with the opinion of our sages in Sifrei 44, as brought by Rashi on Numbers 7:1, “On the day Moses finished building…teaches us that all seven days of the dedication Moses would set it up and tear it down; on that day he set it up and did not tear it down.”

Since the issue of chronological order in the Torah has implications for learning the methods through which the Torah is explicated (as we shall see below) we should stop and explain it better.

Numbers 1:1 begins, “And the Lord spoke to Moses in the Wilderness of Sinai in the tent of meeting on the first day of the second month [Iyar] in the second year after they had gone out of Egypt, saying.”

Later on, in 9:1, “And the Lord spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai in the second year after they came out of the land of Egypt, in the first month, saying.”

The Gemara in Pesachim 6b asks “Shouldn’t it have been written first about the first month and then about the second month? Rav Manasia the son of Tachlifa, in the name of Rav: This means there is no chronological order in the Torah.” Rashi explains, “The Torah was not precise about chronology, and the sections which were dictated first were placed before those which came later.”

We learn that “the holy one, blessed be He, spoke and Moses wrote” (Baba Batra 15a) means that he would write each portion in a different scroll. But in Gittin 60a it is said: “Rabbi Johanan in the name of Rabbi Banaeh said that the Torah was given scroll by scroll.” Rashi explains: “And as it was said, portion by portion, Moses would write it down; at the end of 40 years, when all the portions were finished, he put them together and sewed them with sinew.” And when he sewed them together at the end of 40 years he changed the order of the scrolls and mixed up the chronology.

Not only is it strange to confuse so the readers and those interested, see what stumbling blocks can be set for those who learn halacha and for religious arbiters. The Gemara in Pesachim 6b deduces that the method of general and specific (klal ufrat) is learned from the order in which the holy one, blessed be He, told Moses and not the order in which Moses our teacher put the things. Therefore it concluded that we cannot use this method on two issues, but only on one issue where Moses did not mix the order up and wrote as he was told. “This means that there is no chronological order in the Torah. Rav Papa says this is only said about two issues, [two sections, according to Rashi], but on one issue [one section] he put the first thing first and the later thing later. For if you do not say thus, there is no method of general and specific, for it may be as well specific and general (prat uchlal).” Rabbeynu Hananel explains thus: “Like ‘And if a man from among you shall offer a sacrifice to G-d of an animal [the general: all animals], from the cattle and the sheep’ are the specific, and there is naught in the general that is not in the specific; cattle and sheep and nothing else. And if you say there is no chronological order in the Torah [on one issue], it may be that ‘from the cattle and the sheep you should sacrifice’ was said first, as [G-d] commanded [Moses], and only then it was said ‘of an animal’.”

So we learn that since Moses mixed up the order of the scrolls said to him, we cannot use the method of general and specific. Who knows how many details and halachot were lost to us because of this confusion? (See Menachot 55b, where the Gemara does not use the method of general and specific since they are distanced one from the other. The Tosfot wrote [3rd reference] “There it is in one section, but here part is in the portion of Vayikra and part in Tzav, so it is two portions and he admits that we do not judge so.”)

To add and sharpen the confusion and strangeness on the matter of the methods through which the Torah is explicated, we will bring an example and you, the reader, can draw the analogy to many other such cases in the Talmud.

In Tractate Baba Kama 54b the Mishnah writes: “An ox and all other animals are the same when it comes to falling into a hole and the Sabbath [not being allowed to work an animal on the Sabbath], as are also beasts and birds, etc. Therefore, why does it say ‘an ox or a donkey?’ For the Torah spoke of the common state of matters.” And let us look at the prohibition against working animals, beasts, or birds on the Sabbath. It is written in Deuteronomy 5:14: “Do not do any labor, you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your ox or your donkey, or any of your animals…” Any reasonable person would understand that “your animals” does not mean only oxen and donkeys, but that you must afford Sabbath rest to any animal which you possess. Decide for yourself: why does the Scripture specifically declare the donkey shall rest but the horse should work? How is it possible that the Scripture declares the ox shall not work but the camel should? How has the camel sinned? But the Scripture spoke of the common state of matters, just as the Mishnah itself says, as brought by Rashi on Exodus 21:28, “And should an ox gore–it is the same be it an ox or any other animal or beast or bird, but the Scripture spoke of the common state of matters” and did not necessarily mean an ox.

Another example of this type of wording is from Sanhedrin 67a: “Our rabbis said: ‘a witch [shall not live], be it male or female. Therefore, why did the Scripture use the female? For it is mainly women involved in witchcraft.” (Rashi, on Exodus 22:17, says, “A witch shall not live but shall be put to death by the religious court. It is the same, be it male or female, but the Torah spoke of the common state of matters, for it is mainly women involved in witchcraft.”)

But the Sages of the Talmud, who interpreted the Mishnah, strayed from accepting the plain and explicit text of the Mishnah (that the Torah speaks of the common state of matters) and used the exegetical methods. This is one of the most strange things found about Chazal, and we do not know why they strayed from the common sense, for in this case the halacha, based on the plain text, does not differ from their exegetical conclusion, so why should they abandon the plain, clear text?

Thus the Amoraim learned in the Gemara that no animals may be worked on the Shabbath, using the method of general and specific and general (klal ufrat uchlal). In the Ten Commandments, in Exodus 20:10, it says, “Do not do any labor,… and your animals…[general, including all animals].” When Moses repeated and changed the Ten Commandments in Deuteronomy 5:14, he said, “Do not do any labor,…and your ox and your donkey [specific] or any of your animals [general]…” The scripture writes the general, the specific, and again the general. Since the specific [the ox and the donkey], are animals, the rule is the same for all animals.

But the books of Exodus and Deuteronomy are two vastly separated sections, and the Tosfot asked this question on Baba Kama 54b, first reference, “This is not considered a general and specific separated one from the other, for the first and last are as a single word, for ‘remember’ and ‘observe’ (‘shamor’ and ‘zachor’) were spoken as a single word.” The words of the Tosfot are difficult, for if they were said as a single word, how shall we know which came first, or were they said together? How can we discuss general and specific and general about that which was said simultaneously? We have already clarified above that the method of general and specific is learnt based on the order of G-d speaking to Moses and not the order of Moses writing the things.

See what Ibn Ezra wrote about the duplication of the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20:1: “We have first read this portion, the portion of “And Jethro heard,” and later the portion of V’etchanan, for at first…and from the beginning of ‘Remember’ until the end of the Ten Commandments there are changes all over the place; in the first it says ‘remember’ and in the second ‘observe’…[and he interpreted the difference between the two sections thus] and now I will speak of ‘remember’ and ‘observe.’ Know that the reason [the meaning and intent of the word] is retained, not the words…for the Ten Commandments written in this portion are the word of G-d without any addition or diminishment, and only they were written on the Tablets…[as opposed to the opinion of Chazal, that the first set of words were written on the first Tablets and the second on the second, see Baba Kama 54b] and the Ten Commandments written in the portion of V’etchanan are the word of Moses. The absolute proof is that there it is twice written ‘as your Lord, G-d, commanded you’.” Ibn Ezra said something amazing: the second set of Ten Commandments are not from the Divine Glory, they are the words of Moses! If so, “Observe and Remember were said as a single word” never was! Also, the tradition that every letter in the Torah was written by Moses from the mouth of the Divine Glory hasn’t a leg to stand on. See Ibn Ezra’s bravery and his devotion to the truth, to write so without fear.

And about the methods through which the Torah is explicated: If Moses repeated G-d’s words without being careful to quote exactly, but was satisfied that the meaning did not change, how is it possible to use the method of general and specific and general?

And you, read attentively the Gemara in Baba Kama 54b up to the end, and see that the Gemara rejected finally the method of general and specific, and learned the prohibition of working all beasts and animals on the Sabbath from the addition of “and all your animals.” From this you learn that the methods through which the Torah is explicated are from the Sages’ knowledge only, and therefore they can reject them. Were the methods handed down from Sinai, how would it be possible to reject them? (Look at all the debate in the Gemara, and you will see that the methods through which the Torah is explicated, which are the main part of the Oral Torah, are often things far from the common sense.)

Since we are dealing with Tractate Baba Kama, we will quote the Gemara’s words on page 54b, “Rabbi Hanina the son of Agil asked Rabbi Haya the son of Abba: ‘Why was ‘well’ (‘tov’) not said in the first set of Commandments, and in the last set ‘well’ was said [‘that it may go well for you’]? He said to him–until you asked me why ‘well’ was said, I asked whether ‘well’ was said or not, for I do not know if ‘well’ was said or not.” Of this the Tosfot wrote, on Baba Batra 113a, first reference, “Sometimes they were not expert on the verses.”

Similarly, in Tractate Berachot 43b: “Rav Papa happened into the study hall of Rav Huna the son of Rav Ika. They brought before them oil and myrtle. First Rav Papa took the myrtle and made a blessing on it, and he took the oil afterwards. He asked him, ‘Does the Rabbi not hold that the halacha is as the third party [Rabban Gamliel, who first blesses the oil] says?’ He answered, ‘Rabba said the halacha is as the disciples of Hillel said.’ But it is not really so, it was only to hide himself that he said it.” As Rashi explains: “Rabba did not say that the halacha is as the disciples of Hillel said, but Rav Papa was embarrassed because he erred and therefore he hid himself by saying it.”

So you have two wonderfully honest pieces of testimony, one that the Sages were not expert on the verses, and the other that to keep from being discovered in their mistakes they lied about halacha and hang the responsibility on someone else to keep themselves from being embarrassed.

See the greatness of those who gathered the words of the Gemara, who wrote it all and did not hide the lack of knowledge and the lies. We, too, shall walk this path without fear or favoritism. We shall say things as they are and shall not fear those who hide things or those who distort things, neither the liars nor the dreamers. For the master of all deeds is knowledge, and the source of knowledge is truth.

Words of True knowledge.