Parashat Acharei Mot

“And if any Israelite or any stranger who resides among them hunts down an animal or a bird that may be eaten, he shall pour out its blood and cover it with earth” (Leviticus 17:13).

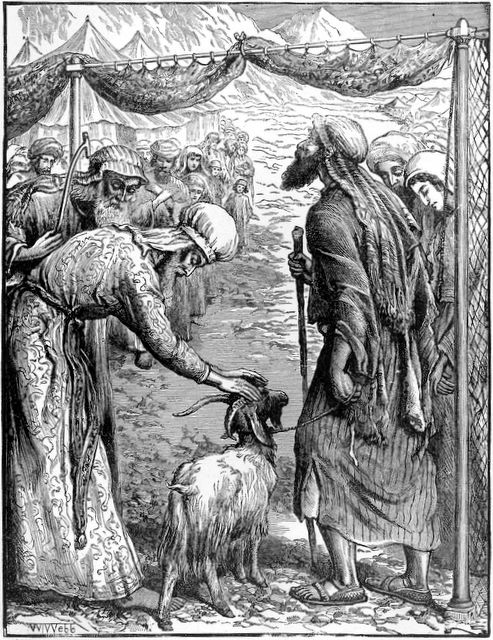

Our portion begins with the work ritual of the High Priest on the Day of Atonement, and is a direct continuation of the portion of Shemini (Leviticus 10). The Scripture there stops in the middle of the topic, goes on to the portions of Tazria and Metzora, and only later returns to the matter at hand. But we already know, and we have said and written in many places that there is no chronological order in the Torah. (According to Rashi this is because he who bound the scrolls sewed them out of order; on this matter see what we have written on the portions of Pekudei, Vayikra, and Tzav.) But here, too, the work ritual for the Day of Atonement is not finished. Where did Moses finish it? In the book of Numbers, 29:7-12, “On the tenth day of the seventh month…you shall present to the Lord a burnt offering of pleasing odor, one bull of the herd, one ram…” Splitting the matter up creates difficulties, and our rabbis were divided on the matter of the ram for the Day of Atonement. In Yoma 70b, “Rabbi says it was one ram, as the one mentioned here (Leviticus 16:5) is the one mentioned in the section of orders (Numbers 29:8). Rabbi Eleazar the son of Simeon says there are two rams, one mentioned here and the other mentioned in the section of orders.” And were G-d scrupulous about the matter of writing, the work ritual would have been in one place and we would have been saved the sages’ disagreement.

But even so, from the Scriptures you learn that the main part of the work on the Day of Atonement was the work of the High Priest in the Holy of Holies. In our day, when there are no priests at their work, how do we atone for our sins? This is why Chazal set up the prayers and supplications, prayers for forgiveness and atonement. All this comes to demonstrate that it is not from the Scriptures that we live, but from the prescriptions of sages in every generation. And there is a hint to our words in Tractate Yoma, whose first seven chapters deal with the work of the High Priest on the Day of Atonement, and only the eighth and last chapter deals with the issues of the fast and forgiveness, to show you that each generation has its own forgiveness and each generation has its own atonement. In ancient days it was, perhaps, as described in the Torah, but in our days it is almost exclusively as determined by the sages. Understand this matter well, for it is one of the foundations of religion.

We have already written, on the portion of Metzora, that the Torah did not have pity on the scribes’ ink; it went on at length on matters which never happened and was brief about the main body of the instruction, such as the matters of family purity. Here, too, we see this sort of a strange phenomenon, that the Torah is brief about the issues of a kosher home. Where was it brief? Specifically on the laws of ritual slaughter.

Where do we learn that one is obligated to slaughter ritually? In Sefer HaChinuch, commandment 451: “‘Then you shall slay of your herd and of your flock…as I have commanded you’…In the language of the Midrash Sifre: Just as consecrated animals require ritual slaying, so do non-holy animals; ‘as I have commanded you’–this teaches that Moses our master was commanded about the gullet and the trachea (windpipe).” (This is also so in Hulin 28a.)

Not only does the verse “Then you shall slay of your heard and of your flock” not tell any reasonable reader anything about the obligation of ritual slaughter, the Scripture taught us the exact opposite (that there is no obligation of ritual slaughter) in Leviticus 17:13, “…hunts down an animal or a bird that may be eaten, he shall pour out its blood and cover it with earth.” From the plain meaning of the Scripture it is permissible to hunt an animal or bird and kill them without ritual slaughter, and this is the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda, quoting Rabbi Isaac the son of Pinchas in Hulin 27b, “Slaughter of birds is not from the Torah, as is said, ‘and pour’ — pouring is enough.” We find that the whole commandment of ritual slaughter, which is faithfully observed in every house and at all times, has no base in the Scripture, but is one of those mountains which hang by a hair!

We have already found explained in Hulin 27a, “Rabbi Kahana said, ‘How do we know that ritual slaughter must be at the neck? It is said, “‘And he should slaughter [veshachat] the calf’ — at the place it bends the neck [sach], purify him [chatehu]…No, but slaughtering at the neck is also tradition.” (Rashi explains that this is tradition given to Moses at Sinai.) We see that Rav Kahana wanted to learn the law of ritual slaughter at the neck from word play (and we have already written quite a bit about Chazal’s habit of determining halacha based on word play) until the Gemara pushed that aside and said that all the laws of ritual slaughter are tradition given to Moses at Sinai. This is the place to point out the words of the Gemara and the Sifrei which we mentioned above: “…this teaches that Moses our master was commanded about the gullet and the trachea (windpipe)…” Why did Chazal wish to learn that there was a tradition given to Moses at Sinai specifically from the Scripture? Hadn’t Rashi already taught us, on Leviticus 25:1, “Why is shmita mentioned at Mount Sinai? Weren’t all the commandments given at Sinai? But just as all the general and specific laws of shmita were given at Sinai, so too were all the general and specific laws given at Sinai.” If so, the laws of ritual slaughter were also included in this rule–go and learn.

Since we are dealing with ritual slaughter, we see fit to mention the view of some religious people who in their innocence think that the slaughter which Chazal mandated for us is a less painful death (even than an electric shock, which kills instantly), and thereby they fulfill the commandment not to give pain to animals. For those it is enough that we recall the gemara in Hulin 121b, “One who wants to eat before the animal is dead (but after the slaughter) should cut a portion, the size of an olive, from the area of the slaughter and salt it well, wash it well, and wait until the animal is dead.” We find that the explicit halacha allows hacking the living flesh of an animal in its death throes and cutting off chunks for eating! Not only that, but because of the large amount of time which passes from slaughter until the animal dies, the Rama wrote in Yoreh Deah, section 67:3, “There are those who say one should be cautious and break the neck of the animal or stick a knife in its heart to bring its death closer, so blood should not be absorbed in the organs.” That is, one who does not do this but only slaughters as we do today forces prolonged pain upon the animal. (The Rama’s reason, too, was not because of the animal’s pain but because of the kashrut, that too much blood should not be absorbed into the organs.) Every merciful person’s heart should boil at the great pain caused to animals here.

We will add another proof to our words. The main issue in the slaughter of animals is cutting both the gullet and trachea, but one is enough by a bird, either the gullet or the trachea, and there is no obligation to cut the veins. Come see the cruelty to animals which the Shulcan Aruch rules in Yoreh Deah 21:5, “If half the trachea is cut [and the bird still lives and is not treifa] if he slaughters it and divides the most of the trachea, it is kosher.” According to halacha it is enough to cut a bit more, to detach the most of the trachea, and leave the bird that way until it dies. Imagine how much pain this bird must suffer, for the additional cut to its trachea will not kill it immediately and will not release it from pain; it suffers a long time until it dies.

Another complaint on this issue: If we were commanded about ritual slaughter because the holy one, blessed be He, pitied animals and wished them to be killed in a less painful manner, then certainly this would have to be the method in G-d’s own house, the Holy Temple. So why did the Torah exempt the bird given as a wholly-burnt offering from ritual slaughter and determine its head must be pinched, as written in Leviticus 1:14, “If his offering…is of the birds…the priest shall bring it to the altar, pinch off its head…” Rashi explains, “He cuts with his nail against the nape of the neck and cuts its neck until he reaches the organs (the windpipe and gullet), and he cuts them”?

From all of these things you cannot help but conclude what we have already written in the portion of Tazria, that the commandments were not given out of mercy or lovingkindness, but to make Israel perform the will of His decrees, be they difficult or merely cruel, to show that they are His servants and those who keep His commandments. Servants should not examine the ways of their Master but be enslaved to him body and soul, and fulfill with resignation and zeal His decrees. And truly, anyone who negates his own self in favor of another and abandons his will and reason and selfhood is a slave; his soul is like dust and he has no individuality. For free people there is nothing more contemptible and despised than a slave who is diligent in his everlasting servitude.

Words of True Knowledge.