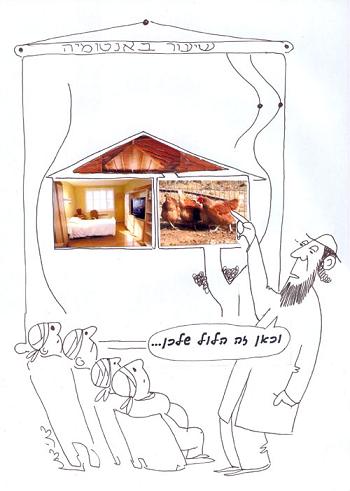

According to the early sages (Tanaaim) a woman can see blood in her vagina from different sources, from the “chamber” (apparently this refers to the uterus, as then she is considered to have niddah impurity and is forbidden to her husband, or from a different source, not her uterus, what they called “the upper chamber,” then the woman is pure. The sages crafted an analogy about women: the chamber, the ante-chamber, and the upper chamber — the blood of the chamber is impure, of the upper chamber pure, and of the ante-chamber, therefore, is suspected to be impure, for it is likely to be from the source (the womb).

The scholars sat and clarified the anatomical reality of the woman’s womb and argued that the chamber is near the woman’s back and the ante-chamber continues toward the stomach. In the middle of the ante-chamber is an opening downward to the vagina from which the blood exits. Above the chamber and the ante-chamber is the upper chamber, as a builder places a brick atop two bricks, with a small opening between the upper chamber and the ante-chamber. They called this opening the “pen.” Therefore, if a woman found a stain of blood in the ante-chamber, inward from the pen, toward her back, she is impure because it is reasonable to assume that the blood came from the chamber, which is an impure source, but if she found the stain of blood in front of the pen’s opening, toward the stomach, she is pure, for we assume it to have come from the upper chamber. According to the sage Rav Huna, if the blood is found behind the opening of the pen, towards the woman’s back, then she is certainly impure, and if the blood stain is toward her stomach, behind the opening of the pen, then she is suspected of being impure. It could be said that the stain came from the upper chamber through the pen to the ante-chamber, which is a pure source of blood, or it could be that the stain came from the chamber and therefore the woman is doubtfully pure,. Doubtfully impure — it can be questioned whether the blood stain came from the upper chamber or the chamber, and due to doubt she is judged stringently and considered impure. One of the scholars, Abaye, asked why blood found in the ante-chamber toward the woman’s stomach is feared to have come from the chamber when blood issuing from the chamber should follow the easy route from the chamber to the ante-chamber to the vagina and not skip over the opening to the vagina form the ante-chamber and continue in the ante-chamber towards the stomach. Abaye argued that one is forced to admit that they feared it came from the chamber because they thought she may have bent, causing the blood to skip over the opening of the vagina and continue on in the ante-chamber. If so, even if the blood is found in the ante-chamber towards her back we should suspect she reclined on her back and the blood came from the upper chamber, flowing towards her back instead of following the easy path to the ante-chamber and thence to the vagina. Because of this question the scholar Abaye ruled that blood should be judged in a consistent manner, based on its location; either it should always be judged based on suspicion of impurity or blood behind the opening of the pen should be certainly impure and in front of it, toward the stomach, certainly pure. The scholars asked: According to the Amoraim blood found in front of the opening of the pen, toward the stomach, is pure due to doubt and bloodstains behind the opening of the pen, toward the back, are impure due to doubt, so we find that ruling are always made due to doubt and never due to certainty. So why did the early sages rule that if blood is found in the ante-chamber it is certainly impure and not impure due to doubt? Answer: The early sages ruled it certainly impure when the blood was on the floor of the ante-chamber, which is the easy route for blood to flow out of the chamber. The scholars ruled blood impure due to doubt when it was found on the roof of the ante-chamber, not in its natural place; therefore one may rule the blood impure or pure merely due to doubt.

(Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Niddah 17b-18a)