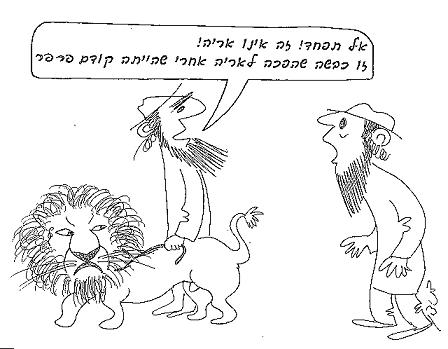

One of the sages, Samuel, ruled that if a domesticated lion ate an animal or a bird in the public domain in the manner of all lions, the lion’s owner is exempt from paying damages for the loss of the animal or bird. Therefore, if the lion in the public domain attacked and then immediately ate a ewe while the ewe was still alive, the lion’s owner is exempt from paying for the ewe, for it is customary for lions to attack and immediately eat the prey. The sages ruled that if animals eat in the public domain according to their habits, their owners are exempt from payment. But if a lion attacked a ewe, killed it, and only later ate it, the lion’s owner must pay compensation for the ewe, as it is not the custom of lions to kill and only then to eat; they eat immediately, while the ewe is still alive. “For tearing it to pieces and then devouring it there is liability to pay.” The scholars asked: Is it not the custom of lions to tear their victims apart and later eat them? We learn from the Scriptures that a lion does tear its victim to pieces and only later eat it: “The lion tore in pieces enough for his cubs” (Nahum 2:13). Answer: It is the way of the lion to kill in order to feed its cubs, but not to kill and then eat on its own. When the lion wants to feed itself, it eats the prey while the animal is still alive. The scholars then asked: From the Scriptures it appears that the lion first kills and then eats, for it is written “Killed for his lionesses.” Answer: The lion kills to feed his females, but he eats his own food while it yet lives. Then the scholars asked: From the Scriptures it appears that the lion kills and then eats, for it is written “Filled his caves with prey.” Answer: It is the way of the lion to kill in order to fill its cave with meat, but when it eats immediately, it eats a living animal. The scholars then asked: From the Scriptures it appears that the lion kills and then eats, for it is written “And his dens with flesh.” Answer: It is the way of the lion to kill prey to bring it back to his den, but when it want to eat immediately, it eats live prey. The scholars asked for the opinion of the sage Samuel: From the early sages (Tanaaim) it appears that a lion kills and then eats, for they ruled that if a lion enters a private courtyard, kills a sheep, and eats its flesh, the lion’s owner is liable for full compensation. This means that the damage caused by the lion is considered its natural and normal way of eating. Answer: The words of the early sages should be understood to mean that the lion killed the sheep to feed it to the cubs, and lions customarily kill animals for their cubs’ food. The scholars then asked: The early sages explicitly wrote that the lion killed the sheep and ate its flesh, meaning that the lion did not take the sheep back to its cubs. Answer: The lion meant to kill the sheep for its cubs, but after the kill changed its mind and ate the sheep itself. The scholars asked: How will we know when the lion kills to place the flesh aside and when it kills to eat? The scholars also asked: The sage Samuel obligated the lion’s owner to pay if it killed a sheep and only later ate it. Perhaps the lion killed the sheep for its cubs to eat but afterwards decided to eat it himself? The scholar Rav Nachman answered that the words of the early sages mean that the owner of a lion which kills a sheep in a private courtyard to place the flesh aside for its young or to eat the sheep immediately, while it yet lives, must pay full damages. Another scholar, Ravina, explained the opinion of the sage Samuel to mean that a lion customarily kills sheep to eat them immediately or to eat it after it has died. But Samuel’s words referred specifically to a domesticated lion which, according to the early sage Rabbi Elazar, generally does not attack at all. The scholars asked: If so, why did Samuel draw a distinction between a lion which attacked a ewe and immediately ate it while it yet lived and a sheep which was killed and eaten after it had died? You must say, said the scholars, that the words of Ravina do not belong to Samuel but refer to a different matter. (The sayings of the sages were handed down orally and though they were familiar to the scholars, the scholars did not always know the context in which they were said. Often a sage’s statement, cited in the Talmud, was made in a different context altogether.)

(Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Bava Kamma 16b)